Shipwreck Summaries

Stories by the Shipload

A gathering of seabed tales trawled from the depths of our local, national and global heritage archives. Enjoy!

80

SHIPWRECKS ON THE DATABASE

7

SHIPS CURRENTLY BEING RESEARCHED

13

VOLUNTEERS

The Syren (1789)

From Jamaica with sugar and rum

‘The Syren’ (1789)

A 380-ton ship, built at Whitby in 1781, the ‘Syren’ was stranded near Beachy Head and lost on 26th February 1789. Under the command of T. Hayman, she was on a voyage from Jamaica to London with a cargo of sugar, rum and other commodities, most of which was lost in the wreck.

As reported in Lloyd’s Register, the ‘Syren’ was owned, either outright or with associates, by Harvey Midforth, from her launch to her demise. He was also master for the first year of the ship’s service, before handing over to J. Knowles by early 1783. Midforth resumed captaincy a year later and probably continued in the role until 1786, before handing over to Hayman.

‘Syren’ was initially engaged in the Baltic trade and the Soundtoll Registers indicate that she brought a variety of cargo back from that region: iron, hemp, wooden stakes, ships’ masts and balks. From Liverpool, one of the British ports from which she operated, she transported up to 300 tons of salt to Riga.

In 1785, she was switched from the Baltic to Transatlantic trade, Lloyd’s List reporting on 13th Sepetmber of that year that ‘Siren’, Midforth, had arrived in the River Thames from Quebec. The lack of aentry inn Lloyd’s Register for 1786 might indicate that she underwent a refit, although there is no corroborative evidence yet.

From early 1787 until her loss in 1789, ‘Syren’, with Hayman as master, plied her trade between Britain and Jamaica, each round trip lasting for upwards of one year.

Paul Howard, September 2024

The 'Vrijhijd' (1788)

Also known as the Freiheit and Vreiheid

This wreck provides ample illustration of the difficulties a researcher might face with non-standardised spelling, misspelling and transcription errors. In contemporary British newspaper reports, the wrecked ship was referred to as the ‘Freiheit’, master Carl Peters; however, as a Dutch vessel, her correct name was ‘Vrijhijt’ of which there are several variations. This spelling is taken from the authoritative Amsterdam port records, as is the master’s name, Car(e)l Pietersen.

On 30th March 1789, the ’Vrijhijd’ sank about 15 miles offshore after being in collision with another vessel, the East India Company’s ‘Lascelles’, a 758-ton ship. At the time, the Dutch ship was travelling from Cadiz to Amsterdam (and possibly thence to the Baltic?) with a diverse cargo of silver coins, indigo, cochineal, Jesuit’s bark, Spanish wool, Buenos Aires cow hides, wood and 130+ tons of salt. Although we as yet have no confirmed data on her size, her manifest indicates that the ‘Vrijhijd’ was considerably smaller than the East Indiaman.

There are three muster rolls for the ‘Vrijhijd’, Carl Pietersen, in the Amsterdam Waterschout (water bailiff) records, with nine or ten crew signed up on each occasion, giving a total complement of eleven including the master. This is consistent with reports that the captain and eight hands made it ashore from the wreck, with the corollary that at least two of the crew drowned.

In the 1790 Lloyd’s Register, ‘Lascelles’ is listed in the East India Company section. Built in 1779, possibly on the Thames, she was originally an 824-ton ship, whose master was R. A. Farrington. Sir A. Hamilton is listed as the ship’s ‘husband’ (meaning controlling manager?) and ‘Lascelles’ was registered for trade with China.

Lloyd’s Register for 1781 recounts that, with T. Wakefield as master, ‘Lascelles’ set out for China on 12th September 1780 (A. Hamilton, Husband). In this year ‘Lascelles’ is listed as a 758-ton ship. In her next LR entry (1783) she is shown as ‘fitting for service’. The following year, ‘Lascelles’ is recorded as having set sail for China on 16th March 1783, while the 1786 Register records a similar commencement on 1st March 1785. For her next voyage, commencing 17th January 1787, R. A. Farrington had taken command.

Paul Howard, September 2024

Spanish silver dollar or 'Piece of Eight' 1735

Saint Peter, 1735

Formerly cited as an ‘unidentified Spaniard’, the ship that foundered on 24th November 1736 near Beachy Head turns out to be the Dutch ship ‘St Peter’. She was en route from Cadiz to Amsterdam, her home port, with a mixed cargo of salt, wool, silver coins and plate, of which the bullion weighed over three quarters of a ton.. Nine or ten of her crew of 21 perished in the incident. Spanish records of the trade between Cadiz and Amsterdam list a ‘San Pedro’ in 1735 and it is feasible that this is the same vessel as that wrecked the following year.

In its Country News section, the Derby Mercury of 3rd December 1736 recounts the following: ‘Seaford 25th November. Last night a ship, which by some circumstances appears to be the St Peter, of and for Amsterdam from Cadiz, was wrecked under Beachy and the master and men all drowned. She was laden with salt and wool and about 30,000 or 40,000 Spanish crowns. The wool is all driven to sea but we are informed a large quantity of the crowns are secured in Newhaven Custom House by the Supervisor of the Riding Officers; and they are in hopes of saving more next tide. Any person concerned may be further informed at the Sussex Coffee house, in Flying Horse Court, Fleet Street’.

The following week the Newcastle Courant carried a report on the aftermath of the wreck: ‘Yesterday, eleven sailors belonging to the St Peter, the great Dutch ship that was cast away on the coast of Sussex on the 24th of last month, richly laden with Spanish wool and pieces of eight, came to Town from Lewes to make complaint of the barbarity of the peasants who came down upon them and in defiance of all opposition they and the Customs House officers could make, plundered and carried off great quantities of their treasure; and that otherwise they could have saved the best part of their cargo. A most inhuman custom, prevalent along the coast, that instead of affording relief to their fellow creatures in the utmost distress, they should at that instant in time take the opportunity to spoil and rob them of what little the more merciful waves had thrown them back again’.

As reported by the General Evening Post on 23rd December, a significant part of the silver was recovered and Mister Tapsfield, a carrier from Lewes, took half a ton to London on 22nd December.

Paul Howard

May 2024

HMS Saltash , 1746

Commander John Pitman and his 14 gun sloop HMS Saltash had been having a successful month against the old enemy, France. On 27th May they had taken the French privateer La Ressource, a snow (a square rigged vessel with two masts) of 8 guns. On 13th June they captured another privateer Le Petit St Benoit and the following day they took L’Alerte. They must have all been looking forward to the day when they received their prize money.

Then on 24th June they were chasing another French Vessel about six leagues off Beachy Head when between four and five o’clock a violent thunderstorm struck and a heavy wind blew the sloop over. Most of the crew, including the captain and his lieutenant George Beaumont drowned, except for a few who managed to save themselves on some oars they lashed together. They were picked up by a Dutchman and put ashore at Eastbourne. Probably about 100 of the crew of 110 died that day.

HMS Saltash had been built in 1742 at Rotherhithe at the shipyard of John Quallet to replace a previous sloop of the same name. She was in the Mediterranean until 1745 and then commissioned for home waters. Quallet also built the next HMS Saltash which was commissioned in 1746.

John Pitman had joined the navy in 1719 as a volunteer on HMS Kinsale. He was then a midshipman on four ships before passing his Lieutenant's examination in 1733. He then served on six other ships before being raised to Commander in 1745 and given the Saltash to command.

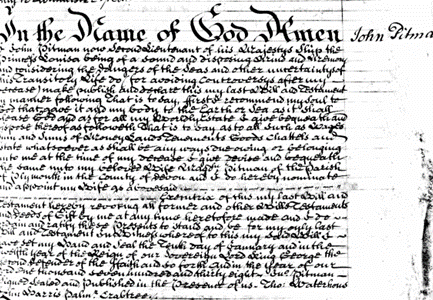

He had married Mrs Magadalene Mignon on 1st December 1738 at Plymouth, Devon. This was while he was between service on the Berwick and the Princess Caroline. They had one daughter born in 1740 called Carolina Susanna Pitman. He made his will while 2nd lieutenant on the Princess Caroline - a very simple one that left everything he had to his wife Magdalen, of Plymouth.

The wreck was possibly discovered 2021. It is noted as being possibly HMS Saltash. 10+ Iron cannon, wooden hull visible under the sand. Many copper bands from powder kegs bearing the broad arrow mark.

Donald Selmes

July 2024

The will of John Pitman

The Prospect, 1751

On the 10th November 1751 The Prospect, sailing from the Canaries to London, called into Plymouth harbour. Her captain George Stockfleet had had a difficult journey returning to Europe from the Canaries because the prevailing winds and currents were against him. It was a busy time for shipping in the English Channel. The Kentish Weekly Post on Saturday 2nd November reported that “Near 100 sail of Merchant Ships homeward bound from Lisbon, Oporto, Seville and the West Indies are in the chops of the Channel”. Chops are an area where tides meet or where a channel meets the sea. When approaching from the Atlantic, the Chops are at the western entrance of the English Channel.

Unfortunately the weather would worsen and violent storms were reported in London and The Sussex Advertiser on 25th November reported that “Thursday night last a violent storm of Thunder, Lightning and Hail …Great number of windows broken , hailstones 2” across.. and a barn full of corn in Willingdon being set on fire.”

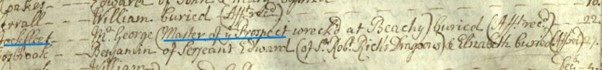

On the 16th November The Propect was wrecked and George Stockfleet died soon after being brought ashore. The burial record entry of St. Mary’s church Eastbourne 22nd November 1751

From St Mary's Church Parish Register-“Stockfleet Mr George ( Master of Prospect wrek’d at Beachy) buried (Afft.rec.d) “

The affidavit certifying compliance with the law had to be made in accordance with Acts of 1666 & 1678 These Acts required burial in a woollen shroud and were passed to support a declining wool trade. Until that time linen shrouds had been used. The Acts were not repealed until 1863.

In the 18th century the main export from the Canaries was wine and trade was largely with London. Wine pressed in September became available in November and so ships returned in inclement weather. Other exports included citrus fruit, cochineal and sugar. While goods sent to the Canaries included linen and metal goods for example pewter and wrought iron.

Sussex Advertiser, Mon 25/11 p4, “We hear that there were two tons of silver on board the wreck, as mentioned in our last, which is all saved and lodg’d at the customs house, that the captain died soon after coming ashore and that one of the sailors was washed overboard and drowned”.

The earlier newspaper report is not available but it is highly likely that this refers to the Prospect as the scenario does not fit any other incident in the area at that time. Unfortunately inventories of goods stored at Customs Houses at that time are not available so we may only wonder.

Valerie Blaber

8th July 2024

A mid C18th brandy bottle of the type imported from Malaga

Good Intent, 1755

On 28th November 1755, Lloyd’s List reported ‘the ‘Good Intent’, Field, from Malaga for

London is ashore near Beachy Head and is like to be lost but most of the cargo will be saved’.

At the time of her loss ‘Good Intent’ had been under Field’s command, not necessarily

continuously, since at least September 1749, when she was reported by Lloyd’s List as sailing

from London to Seville. The round trip, including time in the Spanish port, took over two

months, as evidenced by Lloyd’s List noting that she had arrived in Dover from Seville on

30th November 1749. Her next return voyage, between London and Lisbon, took place

between February 1749 and April 1750*.(*Note: until 1752, the Julian calendar was in use,

in which the year ran from March to March, hence the unfamiliar time line)

From Portugal, ‘Good Intent’ sailed to Ireland via St Martin’s before a round trip to

Southampton. She sailed from Cork to Lisbon in June 1751, arriving back in mid-August. In

her final trip of the year, she sailed from Cork to London, whence Dunkirk, Oporto and

Lisbon.

From 1752 onwards, the focus of trade shifted from Portugal to Spain with Malaga, and to a

lesser extent, Corunna, as the beneficiary ports. At the time of the Beachy Head incident,

Malaga’s principle exports included wine, brandy, citrus fruit and dried fruit.

Paul Howard

- July 2024

Caledonian Mercury 3rd April 1784

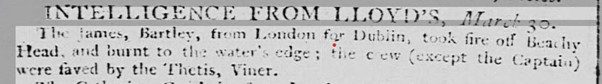

James, 1784

James is one of those mystery ships where we have a record of it having sunk according to the Lloyds

List of 30th March 1784 which reads “"The James, Bartley from London for Dublin, took fire off

Beachy Head, and burnt to the Water's Edge, the crew (except the Captain) were saved by the Thetis, Viner". No further explanation is given of how or why the James caught fire.

No record can be found in the Lloyd’s Registers of any ship named James with a Captain Bartley and

no reports of the wreck have been found in newspapers. The exact date for the sinking is unknown although it would have been in the few days preceding 30th March.

The Thetis was a brig of 220 tons owned by Waley & Co and from Liverpool and built in 1777 and

captained by W Viner since at least 1780. It obviously did not get delayed much by the drama with the James as the Manchester Chronicle reports on 13th April that it had arrived in Liverpool from London.

Don Selmes

July 2024

Uffrow Catherine Maria, 1787

In the winter of 1787 a Dutch Hoy set sail from Malaga for Rotterdam with a cargo of lemons, raisins and Malaga wine. The port at Malaga had been renovated in preceding years and it was now a successful port with a new lighthouse and a recently built promenade.

Unfortunately the Uffrow Catherine Maria never reached Rotterdam; it was wrecked in a storm off Beachy Head on 4th December at a place known as the Three Charles.

With the assistance of people from the shore, in the lull that followed the storm, the crew and most of the cargo were saved.

Some of the crew were very lucky to survive. When people from the shore boarded the vessel they found that some men had broken into the captain’s cabin and were drinking his spirits, they were drunk and fighting while the captain was still trying to save his vessel.

This was the heyday of smuggling and Revenue Officers from nearby Seaford went to inspect and secure the cargo. On their way to the wreck they came across a smugglers’ boat and seized the cargo, mostly foreign spirits. A lucky break for the Revenue Officers!

The cargo of the wrecked Uffrow Catherine Maria would have been a heavy cargo to unload. Each of the 11 butts of wine held 475 litres (with each litre weighing 1.6 kg) and 100 barrels of raisins @ 45 kgs per barrel, and then of course all those lemons!

Valerie Blaber

8th January 2024

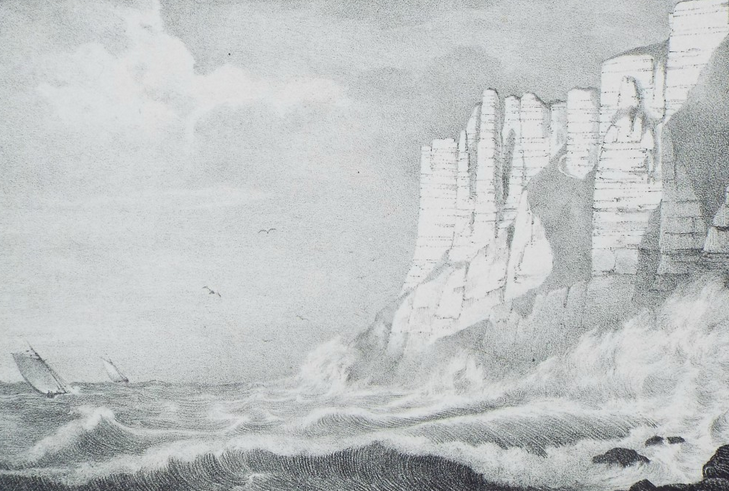

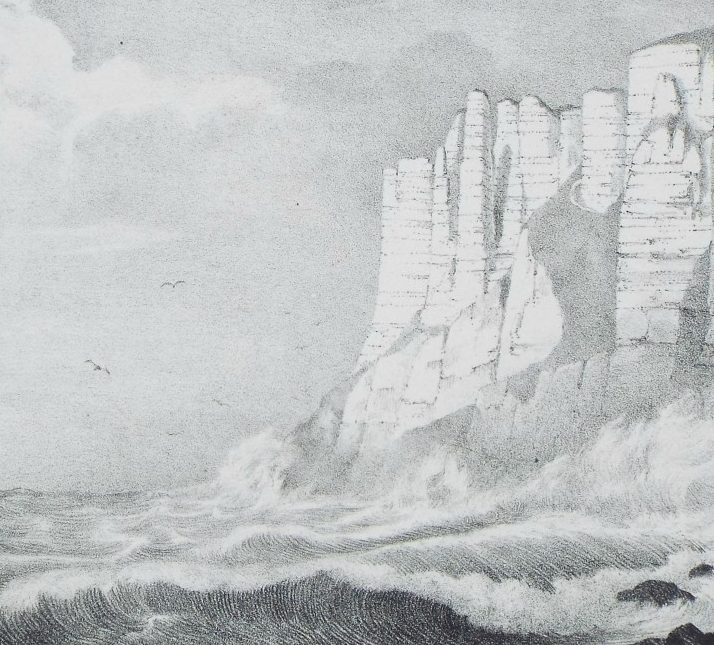

The Three Charles Beachy Head, lithograph by George Lowe (1796-1864)

The Two Brothers , 1790

The 120-ton brig, ‘Two Brothers’, master Edward Theaker, was driven ashore by a storm on the 1st November 1790, while en route from Malaga to London. Of her cargo of 600 crates of lemons, only eight survived intact. Fruit washed up on Eastbourne beach was sold for two shillings per 100. According to a contemporary account, ‘the ship was beaten to pieces’.

Lloyd's List of 27th August 1790 reports that the Two Brothers, Theaker, was in the Downs on 26th, awaiting departure for Malaga, evidently her penultimate voyage. The day before her loss, Two Brothers, Thacker (mis-spelling) was reported at Falmouth from Malaga.

Saunders Newsletter of 15th May 1789 advertised that the Two Bridges (120 tons burthen), master Edward Theaker was chartered to sail from London to Havre on the 25th and anyone interested in freight or passage (for which the ship had excellent accommodation) should apply to the master or Garrett Anderson, agents.

Assuming that it was the same vessel, there are indications that 'Two Brothers' with Theaker as master had been involved in the Baltic trade. Lloyd's List of 7th October 1788 places her at Elsinore on 15th September (arrived from Newcastle). Similarly, on 21st November 1788, the same publication reports the ship at Elsinore from Stockholm on 7th November. These accounts are verified by the Soundtoll Register for 15th September 1788, listing a voyage from London to Copenhagen via Newcastle with a cargo of coal, and for 8th November 1788, which records Theaker in command of a ship carrying iron, boards and tar from Stockholm to Dublin.

Paul Howard

16 March 2024

‘Einigkeit’, 1790

Lloyd’s List of 5th November 1790 records the loss of 'another vessel' close to where the 'Two Brothers' was on shore. The Kentish Gazette of 16.11.1790 confirms that this was the Einigkeit, master Joachim C Paruw, was driven ashore three miles to the west of Beachy Head, en route from St Ubes to Gothenburg with a cargo of salt. Between 1782 and early 1790, the Soundtoll Register lists at least voyages by ships with J.Parow (and variations) as master and it seems feasible that at least some of these records pertain to 'Einigkeit'.

Lloyds register has over 200 entries for 'Einigkeit' and variations ('Enigkeit', 'Enekiet', 'Enigketen') between 1764 and 1793. Only two entries, both in the 1764 register, pertain to 'Einigkeit', the first a 100-ton Swedish brig, built 1761, operating out of Wolgast, the second a 200-ton Danish vessel (1749) whose home port was Apenrade. Albeit with a different spelling ('Enekeit') the second of these ships continued to be listed up to and including 1784. In none of the 200+ is a master named Parow (or variations) listed; however, the 1790 register records 'Enekiet', master J. Parlow. Built in 1774, this 120-ton Snow was in the ownership of Arfvidson and registered for a voyage between Gothenburg and Cork. Arfvidson & Co of Gothenburg appear in the 1778 and 1779 registers as owners of the 'Enigheten', a 140-ton snow, built in 1769, also registered for voyages between Cork and Gothenburg. The different years of build seem to rule out the possibility of the later entry being the same vessel. Apart from the Arfvidson entries, there are only three other entries in which Gothenburg is mentioned within registered voyages, all three being linked to a Finnish vessel, master Lundberg. None of the six Gothenburg entries refer to St Ubes (Setubal), although this port features in registered voyages from Cork for two vessels, one from Stettin, the other Norwegian.

The concept of history repeating itself seems appropriate here as another ship named 'Einigkeit', also skippered by Parow, was stranded near Ostertopp on 18th November 1866 while voyaging from Lubeck to Memel. The crew was saved and some of the cargo recovered. (Shipping & Mercantile Gazette, 22nd November 1866)

Paul Howard

16 March 2024

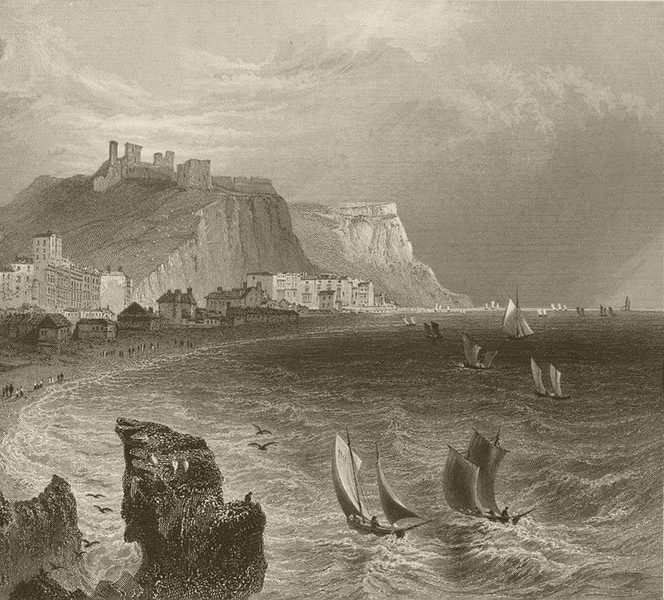

The Three Charles, Beachy Head c1830

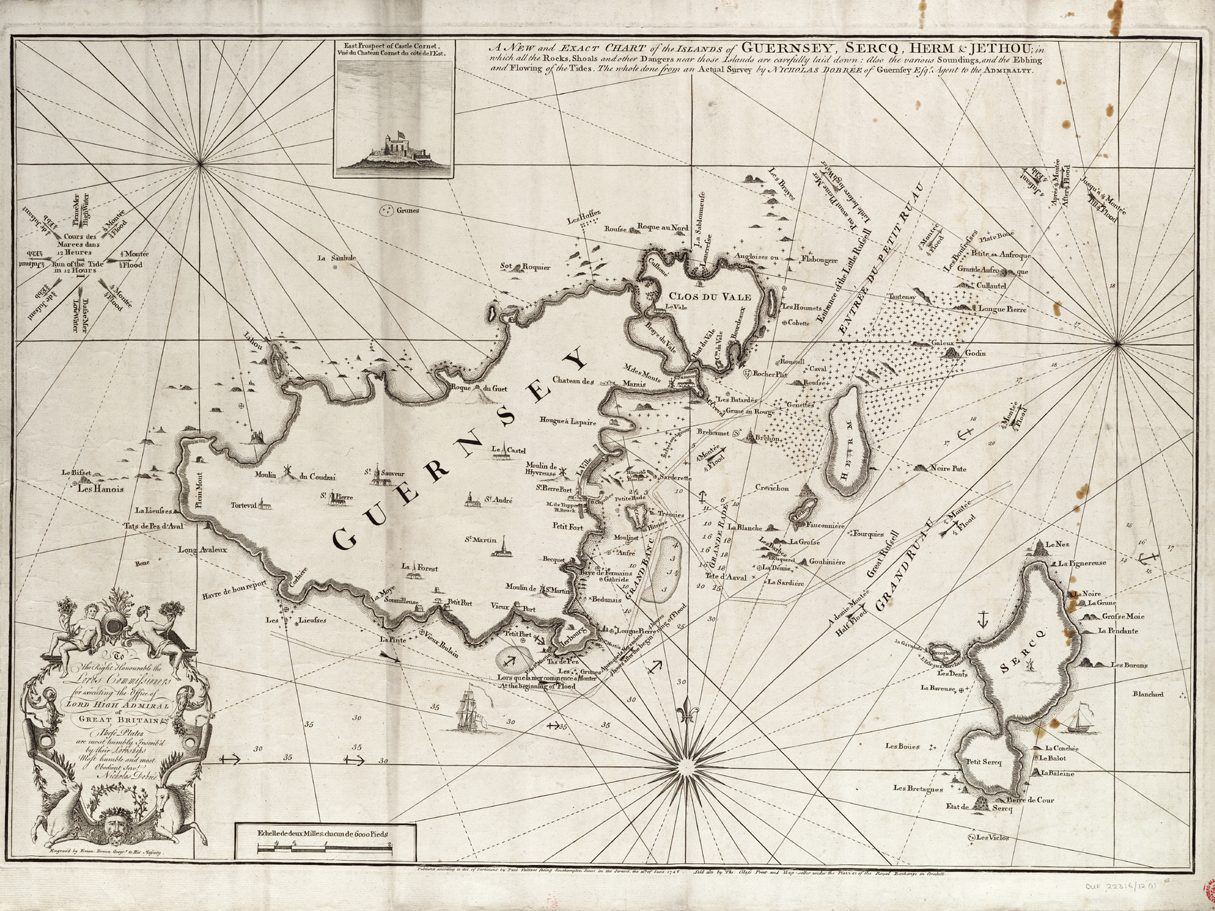

C18th Map of Guernsey

St. Joseph, 1791

The sloop 'St Joseph' was reported in Lloyd's List of 27th September 1791 as 'lost off Beachy Head, crew saved' en route from London to Guernsey. Notice of the ship's penultimate voyage was posted in 'Gazette de L'Isle de Guernsey' on Saturday 2nd July: 'Captain Deschamps, presently loading in London, would like to inform anyone who has merchandise to deliver, that he intends to leave for Guernsey towards the end of this month’.

Between 1783-1791 'St Joseph' is listed in Lloyd's register as a single-deck, 50-ton French sloop with a draft of 8 feet. The crossing out of the 1791 entry, recording Deschamps as master and Isemonger as the owner, marks the demise of the vessel. Rated 'E1', St Joseph underwent deck repairs in 1784 and was registered for a voyage between London and Brest. An almost identical entry appears in LR1790, the exception being that the registered voyage was between London and Guernsey. The 1789 edition notes that captaincy of the ship had passed from Andrews to A. Deschamps; otherwise the details were the same. There being no surviving LR for 1788, the next reference is in the 1787 edition, when Isemonger was the recorded owner and E. Clare the master, a restatement of the 1786 entry. In LR1784 ownership is ascribed to the Captain (E. Clare) and Co. and this is the last year in which the ship was surveyed as 'A1', mirroring the previous year's entry. In 1782 'St Joseph' appears with Clare as captain, Isemonger owner, an E1 rating and a capacity of 60 tons. In the supplementary listing of 1781 Clare appears as master of a different 60-tonner, the British sloop 'St John', owned by Captain and Co. and registered between Guernsey and Hull. The lack of a listing in the registers of 1776, 1778 and 1779, along with missing pages in 1780 seems to indicate that St Joseph was not registered with Lloyds prior to 1782.

In addition to the report of her loss, Lloyd's List contains several references to 'St Joseph'. In reverse order, these are: 5th April 1791, St Joseph, Deschamps, sailed from Gravesend for Guernsey on 4th; 26th August 1788 St Joseph, Andrews arrived Portsmouth from Guernsey, 24th; 18th July 1783, St Joseph, Clare arrived Portsmouth from Lisbon and Jersey 16th (and sailed for London 18th); 19th November 1782, St Joseph, Clare arrived Liverpool from Guernsey, 17th.

Paul Howard

15 March 2024

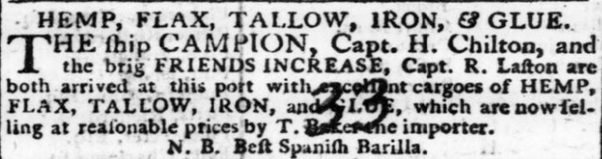

Friends Increase, 1793

The Friends Increase was a brig of just 106 tons, built in Ipswich in 1788 and captained by Robert Laston who was part of a family of sea-going traders. The ship was owned by the Laston family business and based in Ipswich and often voyaging between London and Dublin, although Robert Laston also took her to Rotterdam to pick up spirits and other goods for the East Anglian market.

Little is known of the loss of Friends Increase apart from Lloyds List recording that she was lost near Beachy Heady on her way from Ipswich to Liverpool on 8th January 1793. No mention is made of any deaths although we do know that the captain at least survived.

Robert’s father John advertised in the press the movements of his son’s ship so that he could encourage merchants and tradesmen to buy the goods he traded in. A typical load for the Friends Increase was recorded in 1792 when she was carrying Hemp, Flax, Tallow, Iron and Glue so this was not a glamorous trading ship.

John Laston died in 1789 but Robert and his brother Thomas carried on the business until Robert died in 1803 at Ipswich when he was still only 38 years old. At the time he was master of the schooner Newcastle which traded between Ipswich and Newcastle. He left a widow, Elizabeth, who lived on until 1825 but they had no children.

Donald Selmes

July 2024

LHampshire Chronicle 17th September 1792

Barrels of Bordeaux wine

De Anna Amelia, 1795

A galliot (a small cargo vessel of German or Dutch origin) of 90 tons, de Anna Amelia ran aground near Birling Gap on 12th May 1795, while en route from Bordeaux in France to Lübeck in northern Germany with a capacity cargo of 370 barrels of wine. No other vessels were involved in the incident and, although the weather was unsettled, it does not appear to have been extreme. Consequently, the most likely explanation for the loss was that Anna Amelia struck an obstruction.

The ship’s cargo, most of which was intact, was a magnet to looters, whom the master, Gottfried Volckering, and crew were unable to fend off. When soldiers were dispatched from Eastbourne Barracks to protect the wreck, they too were overcome by temptation before being marched back to barracks to be disciplined. During the salvage operation, disaster nearly struck a second time, for, as the agents and others were clearing the wreck, there was a large cliff fall that brought down an estimated 10,000 tons of chalk.

Anna Amelia’s home port was Stettin in Pomerania, Prussia (modern day Szczecin, Poland), which was also Gottfried Volckering’s hometown. He was born there on 22nd March 1748 and died on 7th August 1809.

On her final journey, Anna Amelia was scheduled to pass through the Danish Sound, where tolls were levied on all vessels entering or leaving the Baltic. A search of the Sound Toll Registers, which record masters, but not their ships, reveals that Gottfried Volckering made multiple voyages through the Sound during the working life of Anna Amelia. Although Gottfried was the vessel’s regular master, the Amsterdam port records indicate that one Gottlieb Looper, also from Stettin, skippered her on at least one occasion, while a second Volckering, Michael, was also employed as a master mariner during the same period.

Paul Howard

4th November 2023

Hope, 1797

The Hope, an armed lugger of 130 tons, with a crew of thirty and 12-14 guns, was hired by the Royal Navy in 1795 to perform a variety of support roles including convoy and intelligence gathering/the delivery of dispatches.

The Kentish Gazette of 8th November 1796 provides insight into Hope’s deployment, ‘Plymouth Nov. 5th, Plymouth. Arrived the Hope armed lugger of 14 guns, Lieutenant Plunket, with dispatches from Corsica and Gibraltar. The Hope saw off Carthagena the Spanish fleet, consisting of seventeen sail of the line and several frigates; they were to be joined by seven sail of the line from Carthagena and then proceed to Toulon, to form a junction with the French ships at that port. The Hope was chased for fourteen hours by a Spanish 74 gun ship’.

In addition to her auxiliary tasks, Hope also engaged enemy vessels, most notably in July 1797, when she recaptured a merchant vessel that had been taken by the French privateer, Vengeur.

On 26th November 1797, while escorting merchant ships westwards through the Channel, Hope, under the command of Captain Rolfe, was run down by the Westindiaman Belfast (master: Grierson) with the loss of eleven lives, the remainder being rescued by the merchantman. Belfast headed for Ramsgate with her bowsprit lost and her foremast sprung.

Paul Howard

8th November 2023

An armed lugger at sea

Pritzler, 1798

On 4th January 1798, 'Pritzler' was stranded and wrecked in a storm and the crew only just

managed to launch the boats before she foundered. With so little time to prepare, the boats

were launched without oars and they were blown into Providence Bay near Rye where they

landed safely. The master was lost and only 200 butts of the cargo (whale blubber) were

recovered.

Built in America (date unknown), she was acquired early in or shortly before 1794 by British

interests and Captain Christopher Foster gained a letter of marque, i.e. a commission to be a

privateer, in February of that year. At this time, ‘Pritzler’ had a crew of twelve and carried 10

6-pounder guns.

The first Lloyd’s Register entry, in 1795, lists as owner T. Pritzler, in whose ownership the

'Pritzler' was registered for voyages between the West Indies and Cork with J. Harpley as

master.

'Pritzler' was among the ships under the command of Admiral Christian which supported the

successful capture of St. Lucia in 1796. Later that year she was bought by Daniel Bennett

(1760-1826) one of the most influential players in the British Southern Whale Fishery;

captaincy passed to a Mr McGowan. At one stage, Bennett owned at least fifteen whalers

and over the course of three generations of the company, nearly one hundred ships, both

whalers and traders, passed through the Bennetts’ hands.

On 10th June 1796 ‘Pritzler’ set out from Deal for the South Seas and her first whaling

expedition. In December she called in at Rio de Janeiro to refresh food and water. On 28th

November 1797 Lloyd’s List reported her arrival in Delagoa (now Maputo) Bay, Mozambique

from the South Seas. Given the sailing time from Mozambique to the English Channel and

the slowness of news from distant outposts, the Lloyd’s List entry clearly refers to an event

several weeks earlier.

Paul Howard

July 2024

Diana, 1803

In May 1803 the sailing vessel Diana set sail for Hamburg from the city of Porto, located on the Douro river estuary in northern Portugal. The most valuable export from Porto at that time was the fortified wine Port but the Diana was carrying a different cargo much in demand in northern Europe, sumac (shumac).

The leaves of this plant were used in the tanning of leather. The process gave soft and supple light-coloured leather from horse, goat or sheep hide. Sumac also has a culinary use and when dried and ground it has a dried gritty texture that gives colour and acidity to dishes.

In 1803 the sailing vessel Diana set sail for Hamburg from the city of Porto, located on the Douro river estuary in northern Portugal. The Diana did not reach Hamburg, it was reported in Lloyds List as “…. lost near East Dean on the Coast of Sussex.” and thus ended the voyage of the Diana on May 26th 1803.

The Portuguese captain was a long way from home and without a ship, which was not an unusual occurrence in the early nineteenth century.

Two months later on Tuesday 19th July this advertisement appeared in The Oracle and Daily Advertiser.

“At the Tiger Inn, East Dean, Sussex on Thursday NEXT, at Twelve o’clock, Duty Free, for the Benefit of the Salvers, ABOUT TWENTY-FIVE CWT. SHUMAC and ANCHORS, Cables and Cordage, saved from the Diana, wrecked at Birling Gap, on 26th May, 1803.”

An Act of Parliament in 1787 had simplified the complexity of customs duties and laws. The customs duty on sumac would have been 1s:5d per cwt. (The daily wage for a labourer was approx. 1s per day.)

Valerie Blaber

January 2024

Sumac in raw and processed form

A cargo of Spanish salt

Carl Salomon, 1805

On Boxing Day 1805, Carl Salomon en route from Alicante to Jakobstad (at the time in Swedish Finland) was driven ashore near Beachy Head by a terrific gale. Although her entire crew survived, her cargo of salt was entirely lost. Recovered items were handed over to the Superintendent of the Port of Newhaven and quarantined.

Carl Salomon was a frigate of 300 tons, built in 1800 at the Carlholmen shipyard in Jakobstad, and named after the son of Adolph Lindskog, one of the town’s principal merchants and shipowners. Although the term ‘frigate’ later applied to specific types of warship, formerly it more loosely described a range of full-rigged vessels. Jakobstad port records confirm the ship’s crew size as fourteen, drawn from the port town and other settlements close to the Gulf of Bothnia.

From the Soundtoll Registers (accounts of the toll which the kings of Denmark levied on the shipping through the Sound, the strait which is the main connection between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea), we can attribute a number of voyages to and from the Baltic to Carl Salomon via records of her master, Jakob Wise. When transporting salt, she routinely carried 140-150 laester of the product, each laest approximating to 2,000 kilograms.

In late December 1801, newspapers reported that, while voyaging from Barcelona to London, Carl Salomon (Wise), having been captured by the Spaniards, had been retaken and carried to safety in Lisbon.

In June 1805, Wise, possibly suffering from a serious illness, took his own life by jumping from a cabin window and the ship’s helmsman, Sven Petterson, assumed command and remained master of Carl Salomon until her demise.

Paul Howard

5th November 2023

Joseph, 1810

En route from Sunderland, possibly to the West Country, the collier Joseph was driven ashore near Beachy Head by French privateers on 24th February 1810 along with the Graces and the Draper, both from Belfast to London. Joseph was dashed to pieces.

As she was not listed in Lloyd’s Register, there is uncertainty about the Joseph’s history, although there are a few contemporary newspaper reports. The Newcastle Courant of 8th February 1806 reports the arrival at Sunderland from London of ‘Joseph’ (master Fisk) with merchandise. It was common practice for colliers to carry other cargoes on their return voyages, as the alternative would be to travel in ballast. Also in 1806, the Hampshire Chronicle of 12th May notes her entering Southampton with coals from Sunderland. Similarly, the Exeter Flying Post of 11th August 1808 reports the arrival at Exmouth on the 10th of Joseph, Fisk with coals from Sunderland, and in December 1809 she is twice is reported as arriving at Ipswich with coals (Ipswich Journal).

Joseph Fisk was born c. 1765 in Walton-le-Soken, Essex and recorded as living in St Osyth, Essex in the 1841 census (ship owner) and 1851 census (formerly a mariner). If the distance between North East Essex and Sunderland appears problematic, it should be noted that Joseph's son, Samuel, moved to Cornwall where he became a coastguard and pilot and several of Samuel's children were born in Ireland. Against a general back drop of the limited mobility of much of the population, perhaps it was in mariners' blood to wander further afield on land as well as at sea.

The fact that Fisk is recorded as a shipowner in 1841 raises the possibility that he was the owner, or part-owner of the ‘Joseph’ and of other ships thereafter. Alternatively, he may have only become an owner sometime after her loss.

Paul Howard

April 2024

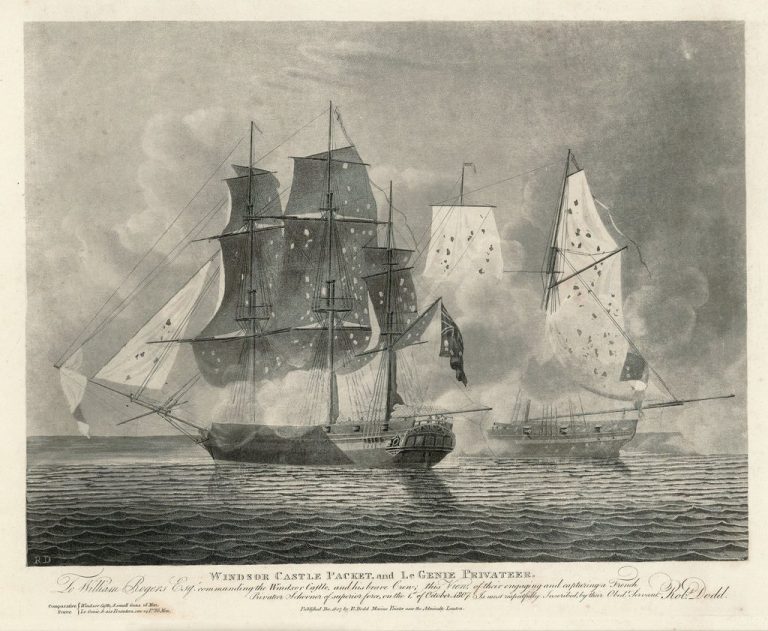

French privateer engaging an English ship

Newhaven Pier and Seaford Bay the Proposed Site for a Harbour of Refuge, Richard Henry Nibbs (1816-1893)

Graces, 1810

On 24th February 1810, while voyaging from Belfast to London, the 163-ton brig Graces was one of three vessels driven ashore near Beachy Head by five French privateers. Owned by Belfast merchant, George Langtry, and skippered by James Caughey, Graces was carrying bacon and assorted cargo at the time of the incident.

Lloyd’s List of 27th February 1810 reported that, whereas the other two ships were completely lost, some of Graces’ cargo was expected to be salvaged. In the event, the ship was also saved, being refloated early in March and taken into Newhaven. Graces continued to trade for at least ten more years, with voyages between Britain and Lisbon added to her domestic activity.

Built in 1804 (at Chepstow), 'Graces' started life as a 150-tonner, her tonnage being increased to 163 by 1808. She was initially owned by Delan(e)y and skippered by Hodgson, with Dublin-Bristol indicated as one of her routes. The Beachy Head incident was not the ship's first brush with near disaster, 'The Cambrian' newspaper (24th November 1804) reporting that 'Graces' from Bristol was on shore on the North Bull, an island in Dublin Bay, before being got off without damage.

Graces’ owner at the time of the Beachy Head incident, George Langtry, was a wealthy Belfast businessman. Born in 1764 at Kilmore. he died at Fortwilliam, his large residence on the outskirts of Belfast, on 17th June 1846. Langtry opened a general store in Belfast c.1786 before making shipping his main business interest. The 1808 trade directory for the city indicates that Langtry had an interest in twelve merchant vessels operating from Belfast to London, Liverpool, where he later established another arm of his business, and Bristol.

The master of Graces from 1806-1811 was James Caughey (various spellings) born 1st October 1770 Portaferry, Co. Down, died 12th April 1832 in Belfast, where he is buried in Clifton Street Cemetery.

Paul Howard

8th November 2023

Draper, 1810

En route from Belfast to London, the 134-ton brig (a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square-rigged), Draper, was one of three vessels driven ashore near Beachy Head by French privateers on 24th February 1810. Built in 1800 and originally owned by H. Haslett, at the time of the Beachy Head incident Draper was in the ownership of Greenlaw & Ware, prominent Belfast owners and agents, and under the command of William Gowan.

With a cargo of linen, bacon and assorted merchandise worth £60,000 (equivalent to nearly £4 million in 2023), Draper initially evaded capture before being boarded by eleven men from one of the privateers, Grand Duc du Berg from Dieppe. Evidently the boarders were unable to control the vessel and it ran aground. While returning to their ship, the boarders’ rowing boat capsized and three men drowned while the other eight were taken captive by the Surrey Militia on shore.

The underwriter’s agent, quoted in Saunders’s Newsletter on 8th March observed, ‘The Captain of the Draper was providentially prevailed on to quit her, as she went entirely to pieces in the night. About 800 pieces of linen have been picked up amongst the rocks and 250 bales of bacon, very much damaged: all the rest of her cargo a total loss’.

As a workhorse of Anglo-Irish trade, Draper carried a wide range of cargoes during her career, but a recurring reference in cotemporary accounts is to her involvement in the export of tea from London to Ireland.

Although Draper was lost, in 1812 Langtry had her replaced by another vessel of the same name, a 147-ton brig (single deck with beams), which was skippered by J. Gowan until at least 1825.

Paul Howard

8th November 2023

Surrey Militia based in Eastbourne, 1810

Henry, 1812

On 15th February 1812, at about 10 o’clock at night the brig Henry was driven on shore under Beachy Head by a French privateer and fell to pieces on the rocks. She was captained by Abraham Reay, travelling from Southampton to South Shields and was carrying a cargo of beech plank, and rails. The crew was saved but the ship (which was insured) and the cargo were lost.

At the time there was some controversy, with the Sussex Advertiser initially stating that the owner of Birling Farm had locked the gates to Birling Gap when there was a right of way for many years and this had hindered the rescue operation. They changed their viewpoint the following week when they stated that the wreck of the Henry was not affected in any way by this issue and the people from the farm had actually sent wagons to help the crew get salvageable items such as the rigging, sails and cables from the ship. It seems that both the current and previous owner of the farm were in the habit of locking the gates so that their wagons were the first ones that could get to ships at Birling Gap to help them and get their reward.

When they talked to the crew they found the Captain was missing and he was eventually found in the tap room of the New Inn in Eastbourne where he said there was not time to get anything away and that the locals should not attempt to do so. The landlady, Mrs Comber, said she thought the man must be in great trouble, and could not mean what he said. As a result the ship broke up without anything being saved. Abraham Reay later denied that this was what had happened and made a legal protest.

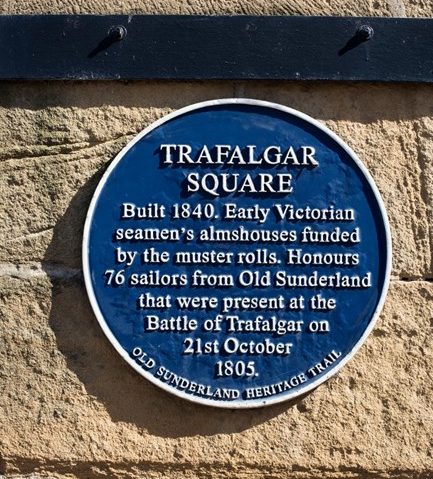

It is likely that Reay was never given a captain’s role again. When he died in 1852 he was living at the Sunderland Aged Merchant Seaman’s Homes at Trafalgar Square, set up for “the relief and support of maimed and disabled seamen, and the widows, and children of such as shall be slain, or drowned in the Merchant Service.”

The Henry was not the only wreck that Abraham Reay was involved in. In 1842 he had first tried to get relief from the Aged Seaman's home with notes against him saying "1842, December Abraham Reay (one of several seamen) of Linnet apply as shipwrecked seamen for 10/- each they having applied in February and for want of a form did not get it. Paid 10/- each." The Linnet of Sunderland, a schooner was wrecked at Portmahomack, Ross-shire on 25th October 1842. Her four crew were rescued. Unfortunately, there was further tragedy when 7 local men and boys tried to salvage the Linnet and all ended up drowning when the ship went down in a storm in January the next year.

Donald Selmes

The English Heritage Blue Plaque at Trafalgar Square, Sunderland

Nimrod, 1813

February 13th 1813 was a tempestuous night and the Nimrod a vessel of 383 tons with a crew of 22

and a captain aged only 18 but described as “a youth of great talent and promise” was driven ashore by force of the wind. Half the crew including Captain Iames Jack were drowned and the remainder only survived by clinging on to a ledge below Beachy Head until the tide went out.

The Nimrod had been launched in Montreal, Quebec in 1809 at the shipyard of David Munn, one of 5 Scottish brothers to have shipyards there, in the same yard and year where the first Canadian steamship, Accommodation, was built. She was re-registered in Greenock, Scotland in 1810 and started on her career in the mahogany trade, sailing a round trip from London to Jamaica to Honduras to Cork and back to London.

A large part of the cargo of mahogany was saved and this was a valuable commodity, being used for good quality furniture across Europe, and Honduran mahogany was sometimes called the only true mahogany.

Furniture and furnishings made of mahogany and manufactured by the greatest woodworkers and cabinet makers in Britain can be found throughout the great houses and castles of

Britain.

England was obsessed with mahogany; imports for 1720 totalled a meagre £42, but by 1753, the figure had risen to £6,430 and continued rising exponentially to £77,744 by the end of the century.

The salvaged mahogany from Nimrod was sold by auction on 5th March near the Cuckmere and

elements of the wreck were also sold the following week.

When the Nimrod had sailed for Jamaica in 1812 the Captain had been a man called Bell but by the time it arrived in Jamaica James Jack was the captain. She left Jamaica on 5th October 1812 and

arrived in Honduras two months later on 4th January. This was at least her fifth round-trip, each one taking around seven months to complete.

A plaque was erected in Ardrossan Churchyard in Scotland, presumably by his father Robert Jack,

also a ship’s captain, which commemorates James’ loss on the Nimrod and the death of his brother Robert at Charleston, South Carolina, aged just 17.

Donald Selmes

July 2024

Honduran Mahogany

Mahogany Chair from around 1810

The collier, "Jane", 1819

When the Jane was wrecked off Beachy Head in October 1819 it would have been one of hundreds of colliers delivering coal that day to ports around our shores. The Jane was on a voyage from Sunderland to Weymouth and on just one Tuesday in October 1819, 216 colliers and other coasters were reported as setting sail from Sunderland, followed on the Saturday by another 174. Before the coming of the railways, passengers would often use colliers for travel south from the north east, particularly to London. This journey would have been quicker, cheaper and more comfortable than travelling by stage coach. Obviously in bad weather it could be uncomfortable and dangerous and the winter of 1819 arrived early and was particularly harsh. A newspaper report of the weather in Brighton on the night of the 21st October states that they experienced a terrible storm “…violent hurricane commenced after 11pm, hail, sleet and snow”.

The Jane was a complete wreck and no coal was recovered but sometimes coal was washed ashore and that was welcomed by the local community.

Sunderland and the Wear River was a thriving industrial area at that time but the river was shallow at the banks. Although work was in progress to improve the navigation of the river the cargo of the Jane may have been loaded by keel men. The keels were shallow wooden boats, which were loaded with coal from a chute on the riverside and then sailed, or rowed if necessary, down river to the waiting collier brig. Here the coal would be shovelled onto the brig. This was an arduous job due to the difference in height of the two boats. In 1819 the keel men had been on strike. They wanted more money when they loaded brigs where the difference in height, between keel and brig, was more than 5 foot.

In 1747 James Cook had started his career as an apprentice on a collier brig out of Whitby, he was so impressed with the sturdy collier brigs that he chose these for his exploration ships, Endeavour, Resolution, Adventure and Discovery.

Valerie Blaber

28th February 2024

Sunderland Harbour, 1864, by John Wilson Carmichael

A typical Brig of 1820, The Lady Nelson

Buffalo or Bacalhao, 1829

On 14th October 1829 two ships came into collision off Beachy Head. The first was the Hebden with

Captain Law at the helm going from London to Mauritius and she survived. The second ship, which

was half the size of the Hebden, went down, quickly filling with water and the crew were saved by

getting hold of the Hebden's bowsprit rigging. The Hebden carried on its way and put the crew of

the second ship ashore at Portsmouth, after which Lloyds List and many newspapers reported on the

event naming the second ship as the Buffalo, Captain Hall, voyaging from Chichester to South Shields.

The only problem with this story was that the Ship was not the Buffalo. It was the Bacalhao (a

Portuguese word for salted cod), a 138 ton brig built in America in 1795, which was owned and

captained by J Hall and was transporting timber from Chichester to South Shields. The only paper

that had reported this correctly was the Brighton Recorder.

This was not the first time the Bacalhao had been in difficulty, although it was then with a different

owner. Bell's Weekly Messenger of 30th December 1821 reported "The Bacalhao, from Shields to

London, was run on board off Winterton, by the Cognac, Barton, and carried away her foremast and bowsprit. Another vessel soon after run on board her, when the crew abandoned her, but she was carried into Yarmouth Roads on Wednesday, the crew having got on board again."

This was not the end of the story. In March 1831 Mr Hall went to the courts to gain compensation for

his loss. He launched an action to recover the value of a vessel, her cargo, freight etc alleging that he

had been run down by the Hebden. The question was, which of the masters had failed in the

performance of the necessary manoeuvres in such a situation. The witnesses on each side attributed

the fault to the want of skill in their opponents, For Mr Hall some witnesses were called to prove that

where vessel has ‘the wind free,’ and meets another ‘close hauled,’ it is the duty of the former to give

way. For the defendant an equal number was called, who proved that where a vessel has ‘the

starboard tack on board,’ she has a right to ‘keep the wind,’ and is, consequently, the business of the

other vessel to give away. The jury had to decide whether the plaintiff’s vessel had been run down by

the negligence and misconduct of the defendant’s servants and if so what was the amount of

damages- Mr Hall had claimed a sum as profit on the goods he had on board. The jury decided in his

favour with damages of £1142 16s.—being the sum claimed, with the exception of the amount

charged as profit.

Donald Selmes

July 2024

Hebble, 1841

On 21st December 1841, Lloyd's List reported that the 'Hebble', Goodill had foundered 10 miles South East of Beachy Head and that all the crew had been saved. She was en route from Newcastle to Le Havre laden with coal, which had been her regular cargo on her southbound voyages for thirty years or more.

The loss off Beachy Head was by no means the first misfortune to strike the vessel, which was built in 1796 and had a capacity of 142-152 tons.

On 21st November 1807 she put into Harwich having lost anchors and chains en route from Selby to London (Hull Advertiser).

On 18th December 1812 the Hull Packet reported that ‘on the night of Thursday last (13th) the brig Hebble from Sunderland, coal-loaden was run on board by another loaden collier off Flamborough Head and received so much damage that three of her people jumped on board the latter vessel in expectation their own would go to the bottom. Almost immediately after this disaster, a third vessel ran on board that which struck the Hebble, but from the darkness of the night the people on board the latter could not ascertain the result of the blow. The following day the Hebble, which had steered to the Northward and hoisted a signal of distress, was boarded by some fishermen from Staiths who took her into Whitby’.

On 8th December 1821, the Star (London) reported that the day before at Newhaven ‘the brig ‘Hebble’ from Sunderland, in attempting the harbour last night struck on a pole and went on shore; she has received considerable damage in her hull and was with great difficulty kept free by pumping; she has been got off and brought in here’.

On 29th November 1838 she put into Harwich leaking, having struck Gunfleet Sand the previous night while sailing from Sheerness to Stockton. (Morning Post)

On 24th December 1839 at Sheerness she broke adrift in a gale and damaged her stern. (Newcastle Journal), on 17th November 1840 she arrived at Ramsgate from Shields for Rouen with the loss of two anchors and chains (Lloyd’s List) and on 4th September 1841 she arrived in Bridlington from Shields for Rouen with the loss of the main topmast (English Chronicle & Whitehall Evening Post).

Goodill (also recorded as Goodall, Goodwill and Goddill) was the tenth or eleventh master in the Hebble’s 45-year service history.

Paul Howard

9 April 2024

Colliers loading, C19th

Hastings, 1842

The Fife 1851

We may wonder how shipwrecked mariners returned home when left without money or possessions. A newspaper report in the Hastings and St. Leonards News of Fri. 9th May 1851 describes one such incident, a hit and run in the English Channel.

At 2 in the morning Mon. 5th May the Schooner Fife, on a voyage from Seaton to Newcastle-upon Tyne, sailing in a moderate breeze from the north, 20 miles distant from Beachy Head bearing E.N.E., was struck on larboard bow by a foreign brig, sailing down the Channel. The bowsprit of the Fife was carried away and anchor torn off, dropping about 100 fathoms of chain cable. The brig that did the damage did not stop, making no attempt to assist the Fife which in 20 minutes filled with water and within two minutes of the 6 crew abandoning ship heeled over and sank. The sea was choppy and the wind against them but fortunately they met the brig James of Bermuda, Capt. Thomas Burrows, bound from Bermuda to London.

This brig took them to Hastings where they landed at 11 o’clock. It was reported that the unknown foreign brig had nearly collided with the James too! The crew of the Fife said that they saw the brig bearing down on them and tried to avoid a collision and although the brig had ample room to change course it failed to do so. The crew lost money and possessions. The men were helped by the Shipwreck Mariners’ Fund Society and Mr Talbot, the station master of the SE Railway Company, gave them free passage to London, in accordance with the protocol of most rail companies. They left by the 5 o’clock train.

The captain of the Fife was Henry Dare and the owner Mr J Head of Seaton, Devon, the following year, in Lloyd’s Register, H. Dare appears as captain of the Carleton, a brig with iron bolts, owned by Mr J. Head on a voyage from Exeter (Exmouth) to Newcastle. It is highly likely that it would have been involved in the coal trade and at that time Mr John Head, the younger, leased a coal yard on Seaton esplanade.

Henry Dare was born in 1805 in Seaton Devon and had certificate no. 38245 as Master, 27th February 1851 Exeter, his certificated service was from 1851 to 1860.

Fortunately for the crew of the Fife the Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners’ Royal Benevolent Society, better known as the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society, had been established in 1839. Her Majesty Queen Victoria was its first Patron and ever since the Society has been honoured by Royal Patronage.

Valerie Blaber

12th April 2024

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.